It’s winter, it’s dark, it’s cold and the perfect time of year for sharing ghost stories, when the thresholds between worlds feels very thin…

The Second Commandment

by Sue Belfrage

I met Kirkby only the once, while we were waiting for a ferry crossing. Rough weather had delayed our boat’s departure and we stood watching waves pound the harbour walls.

‘Sky’s clearing,’ I said, and I pointed to a patch of blue overhead.

Kirkby nodded. He was a tall man, greying, his shoulders somewhat stooped and his expression pensive, as though he bore the world heavily.

‘With any luck, we’ll be on our way soon, if the wind drops,’ he said.

It was biting cold. ‘Fancy a pint while we wait?’ I asked.

Kirkby followed me across the quay to the squat pub overlooking the harbour. We found a seat in the snug and introduced ourselves over our drinks – a pint of beer for me and a glass of ginger ale for him. Kirkby, I learned, was on a pilgrimage of sorts. In measured tones, he explained how he had not long left the priesthood, disillusioned with church politics and exhausted by the demands of his parish. Since then, he had been travelling around Britain, visiting holy sites in a bid to resurrect his faith, which, he said, had been put under enormous strain during the last few years. As he talked, his voice began to falter and tears filled his eyes. I excused myself and went to the bar to buy another round. When I returned, Kirkby had composed himself; for the first time I saw him smile.

‘Anyway, my sorry tale is soon to have a happy ending. A couple of months ago, I returned to an area where I spent part of my youth – a trip down memory lane, if you will. And while I was there, I came across the perfect place to live. A ramshackle, part-furnished little cottage in a hamlet near the town. There’s a pub and a post box, and that’s about it. Nobody knows how old the house is, although by the front door there’s a block of ancient stonework, believed to have been salvaged from a manor belonging to the Knights Templar. But what’s more interesting – for my purposes anyway – are the remains of what appears to be a private chapel attached to the cottage. I think I shall be very happy there.’

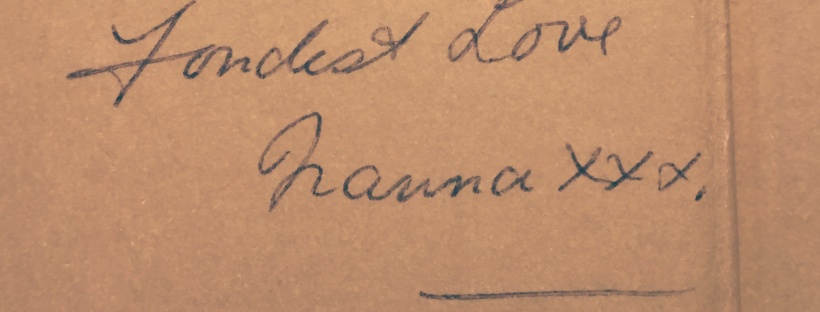

Kirkby’s eyes sparked, and I wished him well. He pulled a fountain pen from his jacket pocket and a scrap of paper from his wallet, and wrote down his address, pressing it on me. Out of politeness I gave him mine in return. However, I did not expect to hear from him once we’d completed our journey and gone our separate ways. I was certainly unprepared for the letter that landed on my doormat a little over five weeks later.

It is an untidy and long document, written in black ink and full of crossings out, smudges and annotations. Its contents occasionally resemble those of a diary, listing everyday trivia. And yet, at other moments, it seems closer to the ramblings of a mad man. You must judge the events it describes for yourself.

***

According to his letter, Kirkby took possession of the keys to his new home on 13 October, not long after our meeting. But the move didn’t get off to an auspicious start: the rental agent was late handing over the keys; the weather was vile and gusty; the front door swollen and jammed; and he was forced to shoulder his way into the hall, where he skidded and landed hard on flagstones wet with rain water that had seeped over the doorsill.

Nevertheless, Kirkby told himself to count his blessings. The air in the cottage was thick with damp, but he managed to get a fire burning in the grate, mopped up the wet floor and shored up the doorsill with a twisted towel. He warmed some soup and sat in the single, badly-sprung armchair to eat his supper, the fire toasting his feet. He prised off his brogues. He would unpack the boxes tomorrow.

Kirkby’s eyelids sank and his head dipped under the weight of his exhaustion. He gave himself permission to doze – when something stirred at his senses. He woke with a start. There was a strong smell of burning and he roused himself from the chair. No sparks had escaped from the fire. He lumbered into the tiny square kitchen; the cooker rings were all switched off. Kirkby sniffed the air again. And again. The acrid tang had gone. He shrugged and went to retrieve his bowl and spoon. As he carried the items to the sink, he paused. The nape of his neck prickled and he turned slowly. He had the distinct impression he was being watched.

He told himself he was simply in need of a good night’s sleep. Upstairs, he made up his bed and, after kneeling down to pray, still struggling to give himself completely to the words, he crawled under the sheets. He slept soundly, waking only briefly, fretting he had forgotten something, that there was something he was meant to find. But then he reminded himself his old life was over. There was no cause for anxiety. He sank into dreamless slumber.

In the grey light of morning, Kirkby opened his eyes and glimpsed a shadow by the foot of the bed. He sat up, blinked and realised he had merely been startled by the fluttering silhouette of a tree outside. In his tiredness, he had forgotten to draw the curtains. He heaved himself out of bed and set about his chores.

Later, having unpacked boxes and stacked firewood beside the hearth, Kirkby rewarded himself with a tea break, and took the opportunity to survey his new surroundings. There was a strip of garden at the back, beyond which lay a tangle of laurels. A short stretch of path led to the building he had instinctively recognised as a chapel, attached to the flank of the cottage. The chapel’s rendering had come away in patches, while green blooms of mould spread up towards two narrow yet ornate windows set high beside the arch-shaped door. Kirkby took a last gulp of tea, set down his mug and went to investigate.

The chapel door was locked, but a large rusty key lay in a recess near the entrance. It seemed strange to leave the key where it could so easily be found – more appropriate to shutting something in than keeping intruders out. After two or three attempts to turn the key, the lock clicked and the door creaked open.

Inside, dankness hit Kirkby like a blow to the chest. As he stopped coughing, his eyes adjusted to the gloom. The chapel had clearly not been used for a long time; it was very cold, like a larder in which the shelves had been stripped bare. An image flashed through his mind of a long joint of meat hanging from a beam, but he pushed the thought aside. There was no furniture, no pews or font or altar; the uneven floor was littered with the leavings of rodents, and the remains of a tumbled nest. When he stepped out of the rectangle of light cast by the doorway, he trod on the brittle skeleton of a bird. The abandoned chapel was a disappointment, a mess.

Kirkby braced himself. Perhaps part of his challenge lay in restoring order to this desecrated site? The chapel should be cleaned up and dedicated once more to the glory of God. That would be the most appropriate course of action.

However, as he stood there, he felt affronted by the overwhelming hostility of the narrow space. He turned to leave, when his eye was caught by a bulky bundle in a corner. The bundle was shrouded in layers of hessian sacking and secured with baler twine. He managed to lift the thing and, as soon as he did so, sensed a change in the atmosphere, as if this was what he had been meant to find.

With nothing sharp to hand, he lugged the object back into the cottage and set it on the stone floor. As he sat there, hacking at the binding with a kitchen knife, Kirkby became strangely gleeful. It was like being a boy again and stumbling upon a hidden present, but here, nobody could forbid him from taking a peek. When he had flicked away the cut twine and eased the sacking down the sides of the concealed object, he inhaled sharply. He had indeed discovered treasure.

It was some sort of ornate cabinet, with two panels opening outwards to reveal, like a glimpse of heaven between parted clouds, a triptych of intricately painted scenes. The paintwork was absolutely filthy, darkened with centuries of dust, the lacquer thick, crosshatched and yellow; but even so, when he peered closely, Kirkby could make out a row of angelic faces. Here was the marriage feast of Cana, the transformation of water into wine. There, the healing of the blind and the curing of lepers. And the raising of Lazarus. The figures were cloaked in dirt yet there could be little doubt they depicted biblical scenes. Kirkby had discovered a portable altar.

The style in which the triptych was painted suggested the altar was very old, possibly medieval. In the top right-hand corner of the centre panel was a minute patch of dazzling blue; if the whole piece were cleaned, it would undoubtedly be a spectacular work. Kirkby knew he ought to inform somebody of his discovery, but the more he looked at the piece, the more it struck him that this was his find – and he was not ready to share his treasure with anybody else. Not yet.

A sudden pressure gripped his shoulder, as if clamped by a hand, and Kirkby sprang to his feet. He took a deep breath. His nerves were taut as wire after his visit to the chapel and his imagination running amok; he would calm himself through prayer. He picked up the altar carefully and placed it on a table under the window, wedging a strip of torn cardboard under the table’s feet to keep it from wobbling. There – he had created a passable shrine.

He went to kneel when it occurred to him that he might as well pray seated. Nobody was watching, at least not a congregation, and his knees were very stiff. He pulled up the armchair and clasped his hands together in devotion. He sat contemplating the triptych for at least an hour, maybe much longer, letting the images enter his heart and wash over his soul. As Kirkby considered the lepers, his skin prickled and he prayed he might never know their suffering. He lingered on a slight female figure in the foreground, perhaps Eve, her naked arms raised in supplication, and sensed an unaccustomed stirring. The scene of merrymakers at the wedding brought a tightness to his throat, the memory of an old, familiar thirst. He reflected on the transformation of water into wine – surely this biblical sanction meant wine was not necessarily a bad thing? Perhaps he could afford a short lapse? It would be a test of character. The row of cherubs grinned in approval.

Rising from the chair, Kirkby was drawn once more to the dash of blue in the middle panel. The triptych’s colours would sing like the angels themselves if the grime were wiped from them. He made a note on another piece of paper of the tasks ahead, and the materials he would need; it had long been his habit to jot things down so he could remember them easily.

The light was beginning to fail by the time he reached town, but he managed to catch the general store before it shut for the night. He selected a bottle of white spirit, some acetone, a roll of cotton gauze; and, as an afterthought, a bottle of whiskey. The woman at the till seemed friendly enough. However, as Kirkby pulled out his wallet to pay, her terrier sprang from its basket behind the counter and snapped at his ankles. The woman caught the dog by its collar and dragged it to a back room, where it continued to yap behind a closed door. Although he was rattled, Kirkby attempted to laugh off the incident. The woman couldn’t apologize enough. ‘I’m so sorry!’ she said. ‘I can’t imagine what on earth’s got into him.’

In the cottage, Kirkby poured himself two generous fingers of whiskey. He gulped them down. The burn made him grimace, but the aftereffect was comforting. A glow filled him.

In a cupboard, he found a pair of candle sticks and a box of candles. He lit two and flicked off the overhead bulb. Cautiously, he set the candles on either side of the altar. The small flames cast unsettling shadows across the triptych, distorting the figures and illuminating strange swells of colour under the patina of dirt. Somewhere in the distance he could have sworn he heard laughter. Then he felt a thin, wet lick of cold at his neck.

Kirkby snapped the overhead light back on and extinguished the candle flames. He put a hand to his brow and realised he was sweating. Perhaps he was coming down with a fever. After lighting a fire in the hearth, he rummaged in one of the remaining boxes and retrieved a torch, then poured himself another measure, smaller this time. Next, he laid the altar on its back and held the torch above it. The angels did not look quite so benign now.

In the kitchen, Kirkby mixed a solution of white spirit and acetone in a cup. He dipped the gauze in the solution and returned to the altar with it. Carefully, very carefully, he cleaned the surface of the central panel, wiping across a face in the gallery of angels. The cloth came away blackened with dirt; and the angel had flown, leaving behind it a grotesque creature. A diminutive, snarling demon. Kirkby dabbed at another face; to his horror, this too revealed not an angel but a beast.

He dismissed the growing chill at his back to concentrate on the triptych, dabbing at scenes, liberating them from stained varnish. Each movement of his hand drew back the veil on his own deception. Where he had seen the marriage of Cana was a grotesque orgy of cannibalism and slaughter; the blind and lepers were not being healed but cruelly tortured; Eve was the sorceress Lilith, and the raising of Lazarus a tormented sufferer on a spit. When he had prayed earlier that day so fervently before the altar, Kirkby had not been contemplating biblical scenes and heavenly wonders, but filling his heart and his soul with the abominations of hell itself.

He felt nauseous. The disgusting object had to be destroyed. And, all the time, he was aware of the growing presence surrounding him in the cottage. The malice he had experienced in the chapel was here with him now, in this house. It was close by, watching, feeding on fear. Overhead, the light bulb flickered twice. Kirkby began to recite the Lord’s Prayer. He relit the candles, moving them from the table to the mantelpiece. He stoked the fire and added more wood. He knew what he had to do, but first he needed to secure a witness for himself and the act he intended to undertake.

***

And that is as much as I can tell you, drawing on the letter I received, which, as I have said, consists of mismatched scraps of paper and sheets of scrawl. The rest is conjecture, based on my visit to the hamlet where Kirkby once lived.

I imagine that once he had gathered his notes, stuffed them in an envelope and addressed that envelope to me, Kirkby set out into the dark night to post his letter. The post box in the hamlet is some 300 yards down the lane, set into a wall next to the pub. He would have hurried along the road, guided by the light of his torch, flinching at every rustle in the hedgerows, wondering if his was the only breathing he could hear. Perhaps Kirkby paused to peer through the pub window at the warmth and laughter within, and – his mouth still dry from whisky – slowly turned his back, determined to complete his task. As he approached the cottage on his return, it must have looked quite cosy, windows aglow; only Kirkby knew what was waiting for him inside.

They did not find a body. Merely charred remains, tinder and ash. The landlord told me it is popularly believed that a piece of kindling caught Kirkby’s clothing as he heaped yet more wood on the fire. I like to think he died quickly. The hearth and the walls surrounding it were completely blackened, but the altar, I understand, suffered only slight scorching along one side. Aside from this, it remains intact. Indeed, the last I heard, it had gone to auction. A specialist market perhaps; for there are always buyers to be found for such articles, such ancient objects of devotion.